8 DAYS AFTER 9-11

At a Buddhist retreat in the West Virginia Hills as the ruins smoked | Sept. 11, 2024

EDITOR’S NOTE: I am reprinting this piece written years ago for my old blog on the 23rd anniversary of 9-11 on this day, Sept. 11, 2024. Here is what it looked and felt like on retreat at a Buddhist monastery in the West Virginia hills, a week after 9-11 in 2001. My apologies if I have misstated or misinterpreted Buddhist teachings better explained by a monk. A shorter version of this piece ran in the Buddhist magazine Tricycle on Sept. 10, 2021.

By Douglas Imbrogno | WestVirginiaVille.com

On thick maroon cushions, forty of us sit in the meditation hall of the Bhavana Society. The Theravada Buddhist forest monastery lies deep in the green hills of West Virginia in Hampshire County. It is a Thursday night, a little cool. Perhaps that is why the bullfrogs aren’t croaking amid the lillypads in the temple pond. Their raspy burps are a usual soundtrack to evening meditation at Bhavana.

An airplane buzzes across the sky as we sit in hour-long silent meditation. Though miles from nowhere, the monastic retreat center lies in the flight path to the airports of Washington, D.C., several hours due east. Usually, there are more planes, one right after the other. But these are not usual times. While the planes come only intermittently this night, the engine sounds pose a challenge to concentration far above and beyond mere noise.

We have come to a four-day meditation retreat devoted to the Buddha’s teachings on “Dependent Origination.” It is a teaching key to understanding how through delusion and ignorance, hatred and greed, we create and keep fueling the spinning wheel of suffering and rebirth. That is to say, the sticky wheel known as “samsara” in Buddhist teachings — a.k.a. reality as we perceive it.

Yet the long-scheduled retreat begins just eight days after the world-shaking events of September 11, 2001. We perch uneasily on our cushions, our minds churning with nightmare images from the horrifying attacks in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Somerset County, Pennsylvania.

We are guided to direct metta, a loving-kindness meditation, to the tens of thousands of shattered family members. The haunted survivors. The Ground Zero eyewitnesses up and down the land. Not to mention the shocked millions upon millions of us who followed along on TV around the planet.

Talk about suffering. Talk about hatred and delusion.

And we do.

We just can’t help having Osama bin Laden and his heartless human missilemen sitting alongside us on the room’s cushions. As it turns out, you couldn’t have picked a better place to be at such a terrible time.

Or a better subject.

‘That is not an unkind thing to do.’

It is the next day. We have all unpacked our belongings in dorm rooms or inside the wooden huts known as “kutis,” (pronounced “cooties”) sprinkled by the dozens across the monastery’s wooded 60-odd acres. While we have settled in for the retreat, our minds are far from settled, as was soon to be demonstrated.

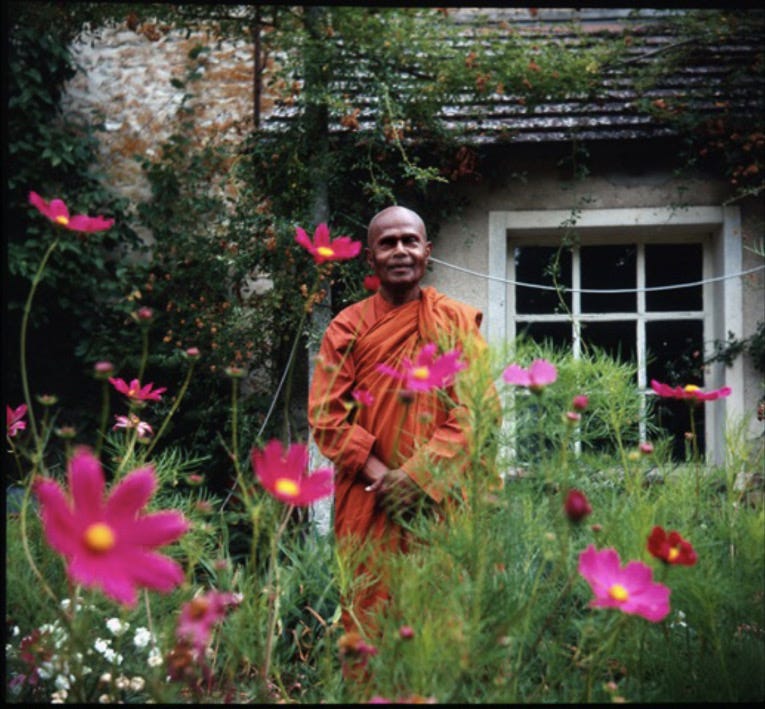

We sit for another hour of meditation starting at 7 p.m. on Friday. We face the head monk and Bhavana founder, Bhante Henepola Gunaratana (known worldwide as “Bhante G”). The Sri Lankan-born monk sits cross-legged on a cushion in front of an altar. The altar is dominated by a 12-foot-high, muscular golden Buddha, serene in his seated meditation posture. Vases hold sprays of fresh hibiscus flowers from the temple gardens.

Bhante G, author of the classic Buddhist meditation primer “Mindfulness in Plain English,” and many other deep, yet accesible dives into the Buddha’s teachings, taps a sonorous chime three times. This signals the end of meditation. The room slowly goes from dark to light, as a younger monk raises the ceiling lights with a slider at the back of the room.

Bhante G rearranges himself, rustling his robes into position, as he prepares to take our questions. But this is a silent retreat, which makes the turmoil of the headlines all the more difficult perhaps.

He is handed a small orange cardboard box full of slips of paper on which we retreatants have written out our first questions of the retreat. Right out of the box, so to speak, jumps Osama bin Laden.

“There are two questions related to, uh … terrorism,” says Bhante G, peering through his glasses at the paper slips. “One is: ‘Is there any way or hope that the terrorists will soften their hearts and have less hate?’”

Bhante G continues reading.

“The second is: ‘I have a lot of fear right now — like from the sound of airplanes overhead. Could you talk about working with this?’

Glancing at the slips in his hands, Bhante G finds a third similar one: ‘Could you talk more about ignorance and volitional formations in relation to the terrorists. What should our country’s response be to this terrible deed?’

“This is unfortunately the disadvantage of having faith placed in a wrong way. Faith in God? They have abused it, and become fanatics.”

“Volitional formations” is a key concept for the retreat and in Buddhist teachings. The phrase signifies those decisive moments in our head — when we cast our vote in choosing wholesome or unwholesome courses of actions. These actions then come alive through our body, speech and mind. And so we instantly create our karma — good, not so good and very, very bad, depending on our volitional formations. The state of our awareness when we form these intentions results in all that we do in the world.

Bhante G cuts to the chase, what with the mastermind and his henchmen who formed the volitions behind the terror of September 11 still on the loose.

“First, I’d like to answer this question. What should we do? We should send some kind of force and capture these people. And put them in jail for life — never release them! That is a very compassionate act! Compassionate toward all other beings and for themselves.”

He pauses.

“That is not an unkind thing to do.”

‘My simple, naive suggestion…’

He goes on to talk about an article someone e-mailed him that week. (Bhante G is a modern monk, who spends lots of time in front of a Macintosh computer while traveling with a silver laptop.) The widely discussed article had run in the online magazine Salon two days after the attacks, a cautionary piece by a self-identified “Afghan-American” named Tamim Ansary.

In it, Ansary counsels that America can’t “bomb Afghanistan back to the Stone Age,” as some enraged Americans may wish. Already been done by the Soviets, Ansary writes.

Make the Afghans suffer?

They’re already suffering, he says.

Level their houses? Done.

Destroy their infrastructure? Too late. Says Ansary in the article:

“When people speak of ‘having the belly to do what needs to be done, they’re thinking in terms of having the belly to kill as many as needed. Having the belly to overcome any moral qualms about killing innocent people.”

Bhante G picks up the theme.

“By killing, there’s no end to that,” the monk says to us. “There are millions of Muslims in the world. By retaliating, by killing, it’s not going to help at all.”

Instead, imprison the terrorists who can be caught, he continues. Educate those among them and their followers who are still able to be educated in human values, not fanatical ones. “Even while in prison,” says Bhante G.

“And give some humanitarian aid and support to those poor people who can become more powerful there. Perhaps through the democratic process, they might overthrow this Taliban government. The poor people are just victims of these terrorists.”

“You remain mindful all the time, you meditate. You try to keep your consciousness clear.”

He pauses. Reaches for a ceramic teacup delivered to him by an orange-robed monk moments before he had been handed the question box. He sips, thoughtfully. Sets the cup to his side.

“This is unfortunately the disadvantage of having faith placed in a wrong way. Faith in God? They have abused it, and become fanatics.”

He sighs, not a sound heard often from the usually forthright, quick-on-the-draw monk.

“I don’t know,” he says, with a light chuckle. “This is my very simple, naive suggestion to this situation.”

It is perhaps asking too much of a Buddhist monk to ask him to offer solutions to what are at bottom political, diplomatic, even sociological scenarios. Bhante G’s real job, it might be said, is to offer guidance and pointers on more deeply fundamental matters. The problems of the mind, for instance, that create such suffering in the world. And how we deal with suffering once it smacks us down. And smacks us down again.

As for airplane engine anxiety, you should not let paranoid feelings overtake you, Bhante G tells us.

“Life is uncertain anyway. You remain mindful all the time, you meditate. You try to keep your consciousness clear.

“Remain mindful all the time.”

‘Let me see your hands…’

I am trying to remain mindful because otherwise I will fall out of the bed of a pickup truck. It is 8 a.m. We have finished our hour-long 5:30 a.m. meditation. After that, we had eaten breakfast in silence with the monks arrayed at the head of the dining room. Now, each of us has an hour of work detail. I have signed up for outdoor work, thinking how much I need to get out of my head. And into my body.

I crouch in the back of a battered Ford truck. The vehicle is piloted by a tall, lanky American monk named Bhante Dammaratana or “Bhante D.” The truck bed is full of logs cut from an oak tree which another monk had chainsawed to the ground and chopped up days before. In a move toward self-sufficiency, the monastery has installed a huge outdoor wood stove the size of a postal van. Its heat warms the meditation hall. The monks refer to it as ‘the Crown Royal,’ which must be its brand name.

But it sounds personal, when they talk about keeping up with the Crown Royal’s enormous appetite for chopped up trees. Selective cutting and hauling of trees on the grounds is a constant task for Bhavana monks and their helpers.

As we drive our load through the woods toward the stove, we pass another monk at the helm of a Kubota tractor. He is using the tractor’s shovel to haul heavier hunks of wood. The tractor is orange, nearly the same color as the monks’ piecework cloth robes, which are the hue of pumpkin pie. The air is cool, the sun golden, the forest deep. How glad I am to be out of the newspaper office where I work and have toiled all week on post-attack follow-up stories!

With gloved hands, I hoist the logs, which smell of earth and rain. I toss them out of the truck bed into a pile where they will later be split and stacked, split and stacked.

“I’d like a word with you later,” Bhante D says as we finish up.

“Do you know this poet, Billy Crystal?”

We are supposed to maintain what is called Noble Silence on this retreat. It is to deepen our mindfulness and avoid “useless speech,” one of my favorite proscriptions from Buddhist teachings (and one of my routine mindfulness misdemeanors). Ignobly, I break the silence to ask the monk what’s up. He tells me he wants to talk about poetry, of all things, and an interview with a poet he had heard on public radio.

“Do you know this poet, Billy Crystal?”

We chew that one over — he’s a comedian isn’t he? It turns out who he actually means is Billy Collins, who was at the time the poet laureate of the United States. Public radio must have sought out Collins’ poetic perspective on the terror attacks. I like this a lot — a Buddhist monk touched by a poet who was talking poetry on National Public Radio. The cosmos doesn’t get more cosmic than that.

I tell Bhante D about an article that I and an English teacher friend had written for my newspaper, to be published that Sunday. It quoted the works of great poets and writers — Auden, Rimbaud, Virginia Woolf, Gary Snyder, T.S. Eliot. The article sought to find in their classic words some guidance and solace in the face of the classic awfulness of September 11, 2001.

“I like Gary Snyder,” Bhante D says of the Zen Buddhist poet.

I promise I’ll mail him the article, which includes Snyder’s poem “The Great Mother” from his Pulitzer Prize-winning collection “Turtle Island.” The poem, in my view, seems to speak to the terrible karmic accounting that I feel — or maybe in my uncompassionate, mindless anger of the moment that I hope — the blood-soaked hijackers and their murderous mentors will face in their future incarnations.

Here is Snyder’s poem, in its entirety:

Not all those who pass

In front of the Great Mother’s chair

Get past with only a stare.

Some she looks at their hands

To see what sort of savages they were.

‘Let’s bomb Afghanistan!’

Later that day, back in the meditation hall, Bhante G suggests bombing Afghanistan. He thinks it’s a good idea. He has picked up on this idea after conferring with friends. He has borrowed a line which has been hopping across the Internet via e-mail upon e-mail.

“We should bomb Afghanistan!” Bhante G announces to us.

Our ears prick up at the mention of bombs out the mouth of an internationally known and beloved Buddhist monk.

“We should bomb them with medicine! Bomb them with food! Bomb them with shelter!”

Later, he turns his attention to the more familiar Buddhist territory of karma, using the word’s less familiar Pali pronunciation of “kamma.” However you pronounce it, the whole ballgame of existence — whether a master terrorist or an average Joe or Jane — it all comes right down in the end to the kamma you create.

Kamma — the wholesome and unwholesome volitions and actions for which we are intimately and ultimately responsible — shapes our destiny. It powers our rebirths. It lashes us tight to the ever-spinning wheel of samsara, the Buddhist word for the cycle of rebirth for time out of mind.

“Our past lives are inconceivable. So many past lives we have had!” Bhante G says.

The life you are now living is the merest fraction of our long wandering through samsara, he says. “In those lives, we have committed so many different kind of kammas.”

In the Buddhist view, we have lived out an unfathomable number of incarnations in various realms of samsara — not only the human realm, but in the animal realm, the celestial realm, the “hungry ghost” realm and the hell realm.

This is another thing I like from Buddhist teachings. Yes, you do have heaven in Buddhism — various heavenly realms, actually. And you will really enjoy this luxury hotel stay for a long, long while. Kick back your heels!

But exactly because you are so dreamy and comfortable, you won’t attend to continued spiritual development. Through inattention, you will eventually exhaust the good karma that got you to these nice places. You will cycle back down through the wheel of samsara’s other, less cozy places.

But there are also hell realms in Buddhism. Not to mention the “hungry ghost” realm, in which greedy, grasping unwholesome karma from your past brings you to ghosthood — you are hungry as hell, for instance, and have a huge belly gnawed by hunger, yet only a pinhole for a mouth. Or you are a wandering spirit seeking the comfort you never had time to offer anyone else.

Yet unlike the hell of Christianity and its old and daunting eternal lake of fire imagery, you will also eventually exhaust the worst of the bad karma that brought you to such an unfortunate incarnation. You will cycle back around the wheel. If your karma is on the upswing, you will be born in the human realm, the best of all possible samsaric addresses.

Why?

Because there is just enough comfort in this realm to allow you the time and concentration to devote to sustained spiritual practice. Yet there is also suffering aplenty as a human being. As we all know. This goads us to seek spiritual answers to the painful questions posed by existence. And if our aim is true, if we are finally able to wake from our habitual delusion, if we can let go of our hatred, if we can let go of our desperate clinging to the things of the world, we can finally escape the interminable round of rebirths in samsara.

The Enchilada of Enlightenment

This is the big enchilada of Buddhist practice. Endless lives in samsara, yes. If you want. But there’s a way out and Buddhas point the way. (There have been many more Buddhas through the aeons than just the one you may be thinking about, although never more than one during any one age. And there are more to come).

Put another way, a Buddha awakens to the enlightenment that awaits anyone once they come to see that it’s really a shell game, this place we call existence, this evanescent thing we call our ‘self.’

That’s where Dependent Origination comes in. I’m not even going to try to explain the Buddha’s radical insight into the illusory nature of reality. I’ll leave that to the monks. That’s why they’re paid the big bucks.

Well, actually, no bucks at all.

But it’s still good work if you can get it.

Or if you get it.

Suffice it to say that when we become enlightened, we break out of the cycle of samsara for good. We awaken to nirvana (or ‘nibbana’ in Pali). It’s a tricky thing to explain and I am not qualified to try. It’s not heaven, it’s not any where, really.

But it is a final end to suffering.

Take it up with a Buddhist monk, if you want the official response. But they’re just as likely to tell you: “Oh, now, just pay attention to what’s going on in your mind right now, this very moment. Nirvana? You can take your tea break now.”

An Enlightened Bin Laden?!?

Yeah, OK. Karma. Samsara. Enlightenment. Sounds good. But what happens, if say while in the human realm, you take a box-cutter, slit a pilot’s throat, and ram an airplane full of other humans into the side of a major landmark in the downtown of a major city, killing thousands of other beings in the process?

The samsaric process works exactly the same, says Bhante G. This means that even major league mass murderers can — far, far down the line of a parade of painful, sorrowful incarnations to come for aeons — achieve enlightenment.

So, wait.

You mean Osama bin Laden could someday become a bodhistava or arahat (these are Buddhist terms for enlightened beings)?

Indeed.

“They themselves have to go through suffering in samsara for long, long periods of time,” says Bhante G, of such factory foremen of evil works.

Then one day, “they will be ready to be humble, simple,” he says. At long last, the worst of their karmic debt paid down, they will be able to hear the siren call to enlightenment — the Dhamma. That is to say, the Buddha’s teachings on suffering. How suffering arises. How suffering ends. And the path that leads to the ending of suffering for good.

And, oh, by the way. That is exactly the same work which the rest of us have to undertake, too. All of us who are not mass murderers in our current incarnations.

If, that is, we want our own experience of suffering to end. If we want to deal responsibly with the suffering inflicted by mass murderers. If we want to deal with our own responses to that suffering. And not create answering waves of suffering. Thus, spinning the wheel of samsara onward.

Same story.

We’re all in this together.

A Question Mark

It is 4:55 a.m. on Sunday. The retreat’s final day has begun. I am dressed and standing just outside the men’s dorm near the edge of the forest. I gaze up. What looks like ten thousand stars hang in the West Virginia sky above North Mountain, at whose base the monastery is located.

A meteor bolts across my line of sight.

I have slept well. My first night on retreat, I’d had a bad dream — car crashes, bodies of children in the road. (One of the side benefits of intense meditation practice is that you may recall your dreams with greater clarity. Fun when they’re good dreams — not so fun with bad ones.) I chalk it up to all the intense news. My mind is doing some weird processing.

I hear a plane. Then, I see its blinking red lights.I track it across the sky.

So, let me tell you how it has gone for me during this retreat.

The first day, every plane I hear in meditation is a potential bomb.

The second day, every plane is a question mark. How have we — the United States, the people on those planes that crashed, the ones who could have been on them such as my loved ones and myself — how have we gotten into such a fix?

The third day, when I hear planes while sitting on my cushion deep in meditation, they are just planes.

Just planes.

I stroll through the chilly air down the stony path to the meditation hall.

For more on the Bhavana Society, visit BhavanaSociety.org. Douglas John Imbrogno is editor of the book “WHAT WHY HOW: Answers to Your Questions About Buddhism, Meditation, and Living Mindfully,” by Bhante G, released in January 2020 byWisdom Publications.

Thanks for the retrospective, a fitting tribute.